12 Ancient Maps That Show Impossible Knowledge

These 12 real historical maps appeared impossibly advanced for their time until modern scholarship revealed the sources behind their surprising accuracy.

- Chris Graciano

- 7 min read

Throughout history, certain maps have startled researchers because they displayed geographic knowledge far beyond what historians believed ancient or medieval societies could access. Some charted coastlines centuries before European contact, others captured continents with an accuracy that seemed to contradict available navigation methods, and still others blended worldviews from multiple cultures long before globalization. These maps revealed that cartographers used trade networks, oral reports, astronomical techniques, earlier source maps, and painstaking observation to achieve results that later generations misunderstood as “impossible.” These 12 maps reflects not hidden technology, but a deeper, more interconnected world than history books once suggested.

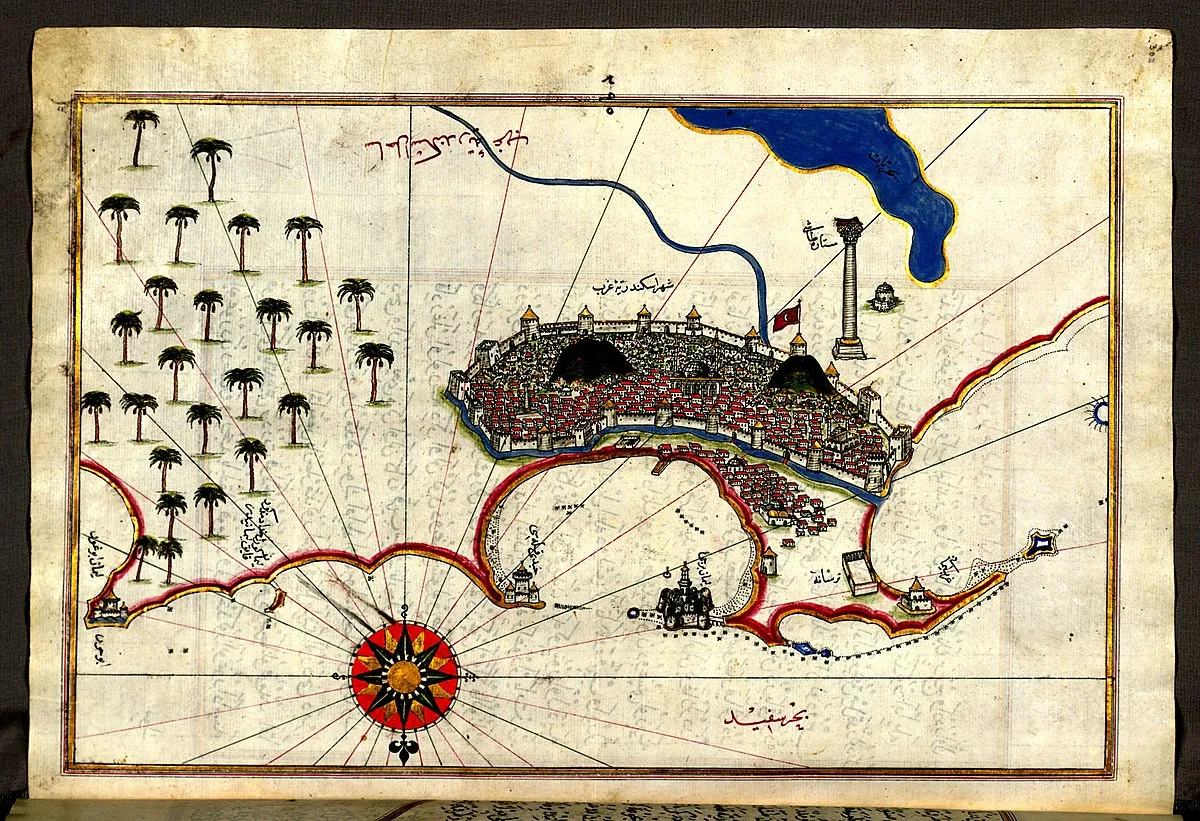

1. 1. The Piri Reis Map (1513) — A Composite of Lost Portolan Knowledge

Piri Reis on Wikimedia Commons

When the Piri Reis map was rediscovered in 1929, many were shocked by its strikingly accurate depiction of parts of South America drawn only a decade after Europeans first reached the continent, leading some to claim it contained impossible knowledge. Modern scholarship revealed that Piri Reis compiled the chart using a remarkable array of sources, including Portuguese portolans, Arabic sea charts, and earlier Mediterranean navigation records that had circulated quietly among sailors. His precision came from synthesizing existing maritime data at a time when most Europeans had not yet mapped the same regions. The map seemed impossibly advanced only because Piri Reis had access to a wider and earlier stream of geographic information than later historians realized.

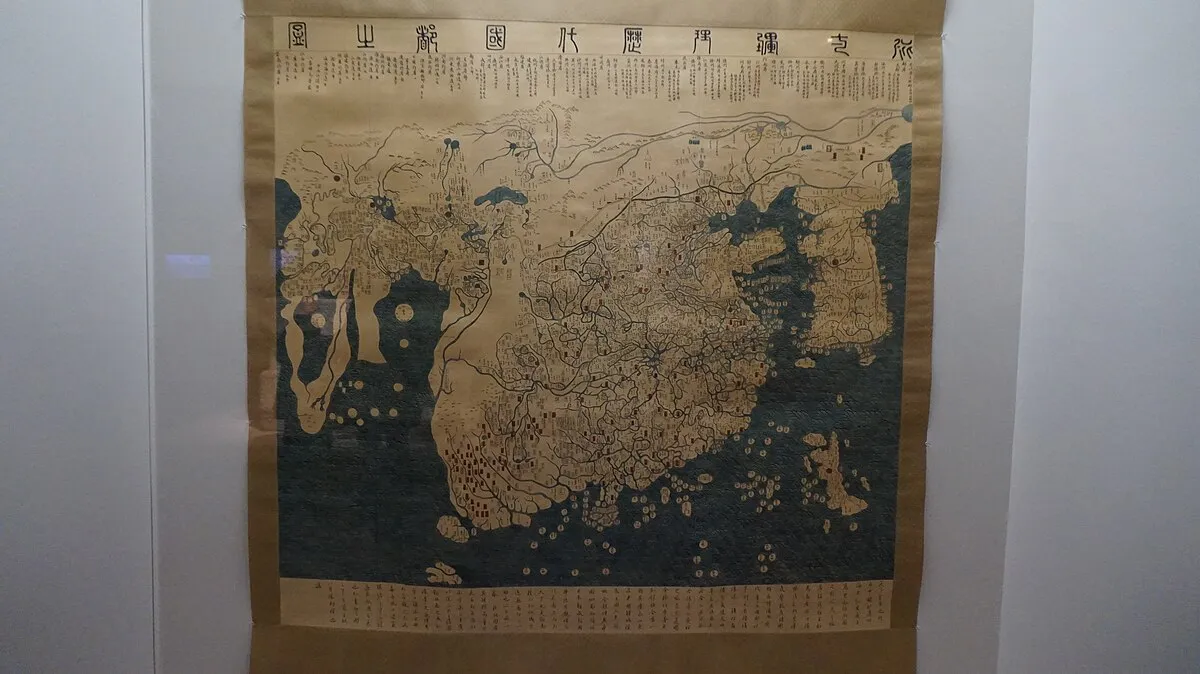

2. 2. The Kangnido Map (1402) — East Asia’s Unexpected Global Awareness

Jocelyndurrey on Wikimedia Commons

The Kangnido Map astonished modern historians because it depicted Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Europe with surprising scale and proportion decades before European world maps attempted similar global coverage. Further study showed that Korean scholars combined Chinese geographic works, Islamic cartography transmitted through the Mongol Empire, and local knowledge to create an ambitious global synthesis. Rather than containing unknown knowledge, the map demonstrated how interconnected Eurasian scholarship was long before Columbus or Magellan. Its “impossible” accuracy simply reflected a world where ideas traveled farther and faster than previously assumed.

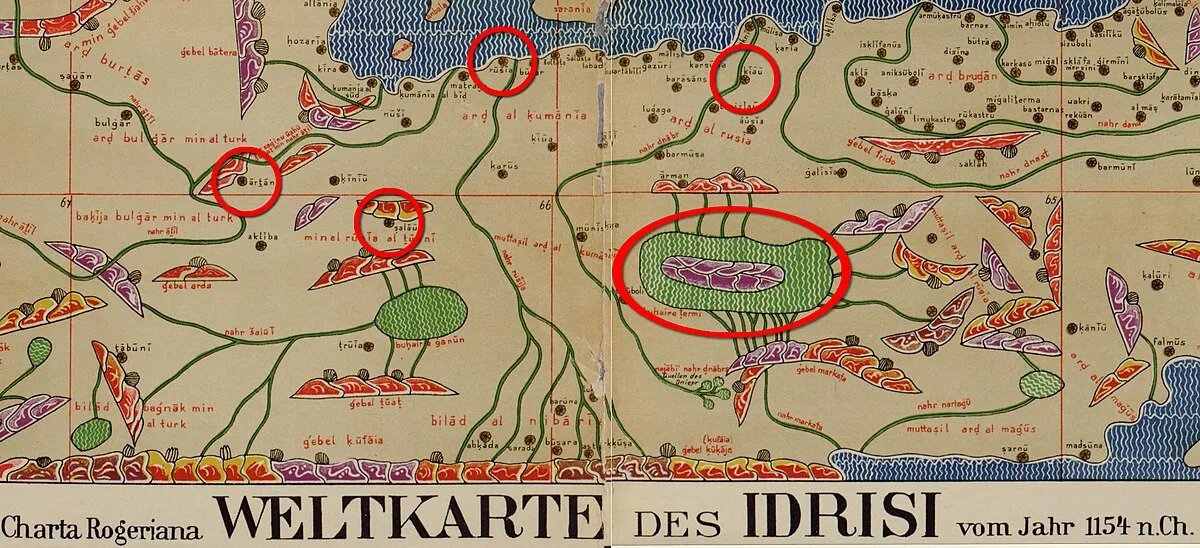

3. 3. The Tabula Rogeriana (1154) — Islamic Geography Beyond Its Time

Idrisi on Wikimedia Commons

Created by the geographer al-Idrisi for King Roger II of Sicily, the Tabula Rogeriana seemed impossibly detailed when compared with contemporary European maps, depicting extensive trade routes, river systems, and coastlines with striking coherence. This was possible because al-Idrisi interviewed travelers, merchants, sailors, and diplomats from across Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean, gathering firsthand accounts unavailable to European scholars of the time. The finished map fused geographic traditions from the Islamic world, Byzantine knowledge, and the lived experience of explorers who had crossed vast distances. It appeared almost supernatural in scope, yet it owed its detail to rigorous data collection across multicultural networks.

4. 4. Fra Mauro’s World Map (c. 1450) — A Globe’s Worth of Detail Before the Age of Discovery

Sailko on Wikimedia Commons

Fra Mauro’s circular world map astonished later historians because it depicted Africa’s southern coastline and Indian Ocean trading networks with a sophistication that seemed impossible for a pre-exploration cartographer. However, researchers learned that Fra Mauro consulted merchant families, sailors from the Indian Ocean, and travelers returning from Venetian expeditions, compiling reports that described routes far beyond Europe’s direct reach. His willingness to trust non-European sources allowed him to portray regions that Western maps had ignored or misunderstood. What looked like prophetic geographic knowledge was actually the result of gathering stories from a truly global maritime community.

5. 5. The Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300) — Myth, Geography, and Surprising Accuracy

Bjoertvedt on Wikimedia Commons

Although the Hereford Mappa Mundi is filled with symbolic imagery and mythological creatures, researchers were struck by how accurately it placed major cities, trade routes, and regions relative to each other despite being created in a largely theological era. Its geographic coherence came from fusing Roman itineraries, Crusader reports, merchant travel accounts, and preserved classical knowledge that medieval scholars continued to circulate quietly. The map seemed impossible only because its makers blended myth and reality without sacrificing empirical observation. It demonstrates how medieval Europeans retained more geographic awareness than stereotypes about the Middle Ages suggest.

6. 6. Da Ming Hun Yi Tu (1389) — A Ming Dynasty Map with Continental Reach

Andrew Neel on Unsplash

When historians examined the Da Ming Hun Yi Tu, they were shocked by its inclusion of Africa, India, Arabia, and Europe, drawn with proportions more accurate than many contemporary European maps. Its precision came from the exchange of geographic information through Mongol trade routes, Islamic cartographic traditions, and Chinese diplomatic missions, demonstrating the intense cross-cultural connectivity of Eurasia. The map was not magical or ahead of its time; it simply incorporated data from cultures that communicated more extensively than later historians realized. Its global sweep reflects a world where information moved surprisingly freely along political and commercial networks.

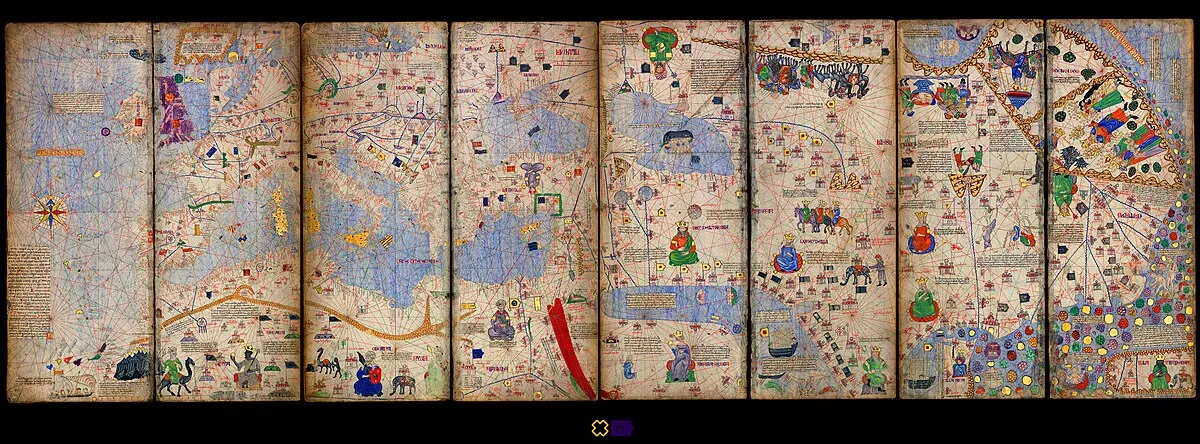

7. 7. The Catalan Atlas (1375) — Navigation Insight Beyond Medieval Expectations

Art Zubov on Wikimedia Commons

The Catalan Atlas contains unusually detailed coastlines, wind patterns, and navigation routes extending from the Mediterranean into West Africa, which once seemed impossible for a 14th-century European map. Scholars later discovered that Majorcan cartographers drew from Jewish, Islamic, and Catalan maritime traditions, compiling reports from sailors who had ventured far along African coasts. Its hybrid style, part nautical chart and part encyclopedic world description, demonstrated a deep understanding of environments far beyond European control. What once appeared improbable now reads as evidence of shared maritime knowledge across multilingual, multi-faith communities.

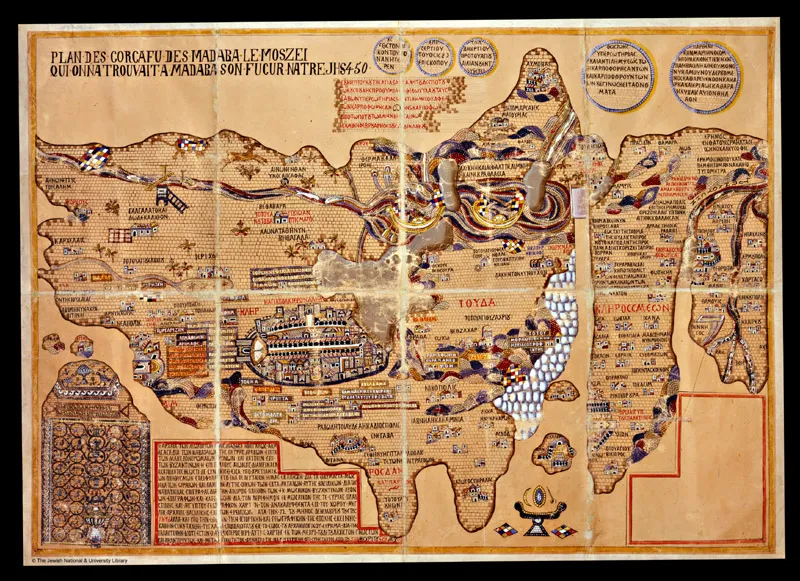

8. 8. The Madaba Mosaic Map (6th Century) — Biblical Mapping with Geographic Precision

The Eran Laor Collection of the National Libary of Israel on Wikimedia Commons

The Madaba Mosaic Map amazed archaeologists because its depiction of places such as Jerusalem, Dead Sea landmarks, and regional towns was so accurate that it helped plenty of researchers locate real archaeological sites centuries later. Its precision came from local surveyors who recorded roads, aqueducts, and landmarks with a level of detail rarely preserved in surviving documents. While created for a church floor, it served as a practical geographic reference embedded in religious art. The map appeared impossibly advanced only because few other maps from the period survived with comparable clarity.

9. 9. The Peutinger Table — Rome’s Vast Road Atlas That Shouldn’t Exist

APB11 on Wikimedia Commons

The Peutinger Table baffled early scholars because it illustrated an interconnected road system stretching thousands of miles across Europe, North Africa, and Asia with extraordinary continuity for an ancient world without telecommunication. Its accuracy arose from Roman infrastructure itself — surveyors, military reports, postal stations, and administrative records that allowed cartographers to map territory with logistical efficiency unmatched until modern nation-states. The elongated layout seemed strange, but it was designed for practical travel planning rather than geographical proportions. What once seemed like impossible knowledge was simply Rome documenting its empire with bureaucratic thoroughness.

10. 10. Zheng He’s Navigation Charts — Oceanic Reach Before Western Exploration

Vmenkov on WorldHistory

The navigation charts associated with Admiral Zheng He appeared impossibly detailed when Europeans first studied them, showing islands, currents, and routes across the Indian Ocean with remarkable confidence decades before Western expeditions charted similar waters. However, these maps were built on centuries of Chinese maritime tradition, incorporating astronomical navigation, monsoon-cycle knowledge, and firsthand logs from earlier voyages. Their precision revealed how advanced Chinese seafaring had become by the 15th century, long before European powers reached comparable range. The “impossible” clarity was a testament to cumulative experience rather than mysterious technology.

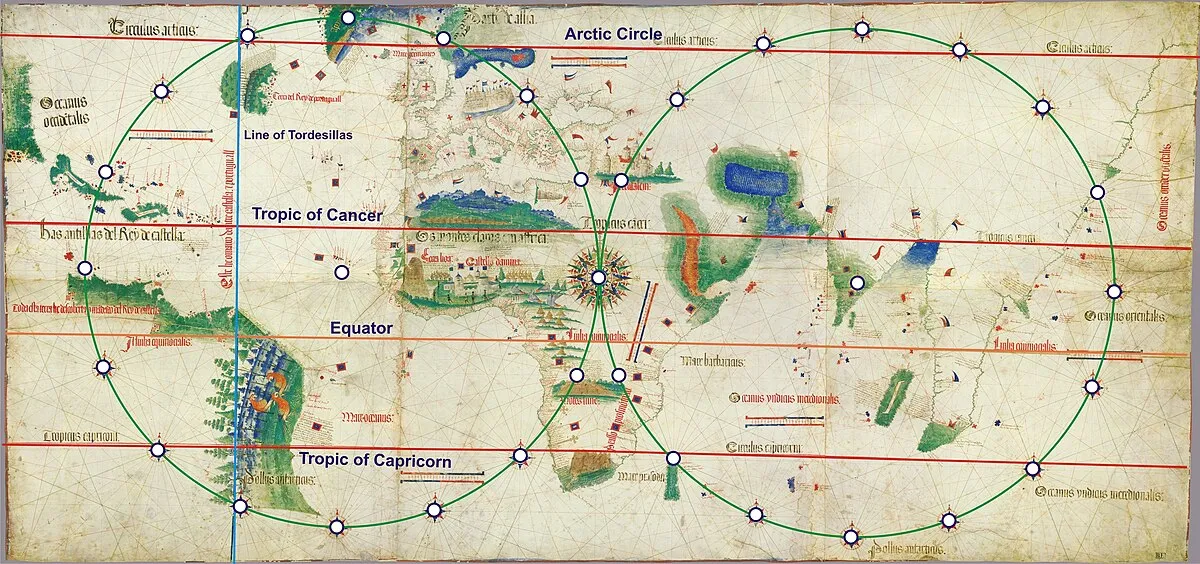

11. 11. The Cantino Planisphere (1502) — A Shockingly Accurate Early World Map

Alvesgaspar on Wikimedia Commons

The Cantino Planisphere surprised plenty of historians because this map depicted the coast of Brazil and parts of Africa with a precision far exceeding what Europeans had supposedly mapped at the time. Researchers later discovered it was based on stolen Portuguese navigational data, which represented some of the best-kept geographic information around the world. This espionage-driven map gave Italy early access to insights on what Portugal did not intend to share with anyone. Its apparent impossibility came not from advanced technology, but from political secrecy and maritime intelligence-gathering.

12. 12. The Borgia Map (c. 1450) — Mythic Imagery Concealing Real Geographic Reach

Dodolulupepe on Wikimedia Commons

The Borgia Map looked impossibly global at first glance because it displayed continents and oceans with an unusually wide scope for a pre-Columbian European work. While the map was filled with mythical beasts and cosmological symbols, scholars realized its geographic framework incorporated information from travelers returning from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Its combination of imagination and empirical detail made the map appear prophetic when later discoveries aligned with its basic structure. It stands today as evidence that medieval cartographers possessed far more global awareness than commonly believed.