15 Archaeological Discoveries That Defy Human History

Here's a look at real archaeological finds that forced researchers to rewrite long-standing assumptions about human origins, technology, migration, and culture.

- Chris Graciano

- 9 min read

Every so often, a discovery emerges that doesn’t just fill a gap in the record but completely reshapes the story of human history. These finds challenge timelines, overturn accepted theories, and reveal that ancient people were far more capable, widespread, or inventive than scholars once believed. From temples thousands of years older than expected, to DNA evidence revealing unknown human species, to ancient cities hiding engineering sophistication rivaling later civilizations, each discovery forced researchers to rethink what humanity was doing and when. This list highlights 15 real archaeological breakthroughs that didn’t merely surprise historians; they redefined entire eras and showed that the past is far stranger and more complex than once imagined.

1. 1. Göbekli Tepe Proving Monumental Architecture Existed Before Farming

Klaus-Peter Simon on Wikimedia Commons

When Göbekli Tepe was uncovered in Turkey, archaeologists were stunned to find massive stone pillars and carved enclosures dating to around 9600 BCE, thousands of years older than Stonehenge or the pyramids. The people who built it were still hunter-gatherers, yet they created coordinated, large-scale architecture previously believed impossible without settled agriculture. This overturned the long-held assumption that farming came first and monumental building followed, forcing historians to rethink the origins of organized religion, labor specialization, and social complexity. Göbekli Tepe revealed that early humans could mobilize enormous collaborative projects long before villages and crops defined human life.

2. 2. Denisovan DNA Showing an Entire Human Species Was Missing From History

digitale.de on Unsplash

In 2010, a small finger bone found in Denisova Cave in Siberia revealed genetic material unlike that of Neanderthals or modern humans, proving the existence of a previously unknown human species: the Denisovans. Even more surprising, their DNA lives on in modern populations from Asia and the Pacific, showing they interbred with early Homo sapiens in ways completely absent from the archaeological record. This discovery forced scientists to admit that the human family tree was far more tangled than the simple three-branch model once taught in classrooms. The Denisovan genome reshaped our understanding of human migration, adaptation, and even immunity, revealing relatives we never knew existed.

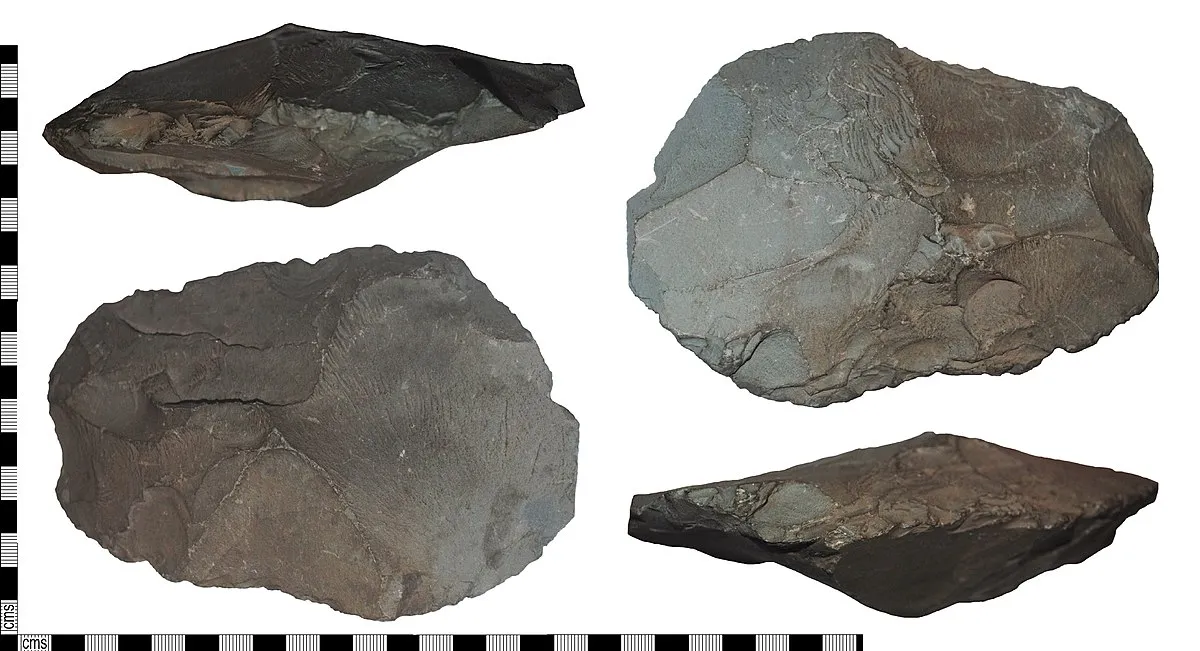

3. 3. The Oldest Known Stone Tools Predating Humans Themselves

The Portable Antiquities Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum on Wikimedia Commons

At Lomekwi 3 in Kenya, researchers uncovered stone tools dating back 3.3 million years—hundreds of thousands of years older than the earliest known Homo species. This meant tool-making wasn’t exclusive to humans or even our direct ancestors, challenging the idea that complex planning and motor coordination originated with Homo habilis. Instead, earlier hominins—possibly Australopithecines—were shaping tools long before traditional timelines allowed. The discovery expanded the definition of intelligence in early species and showed that technological behavior began deeper in evolutionary history than anyone expected.

4. 4. L’Anse aux Meadows Proving Vikings Reached North America First

D. Gordon E. Robertson on Wikimedia Commons

For centuries, European arrival in the Americas was assumed to begin with Columbus, but the discovery of L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland revealed an undisputed Norse settlement dating to around 1000 CE. The site included iron-working, boat repair areas, and unmistakably Scandinavian building styles, demonstrating that Vikings crossed the Atlantic nearly 500 years before Columbus. This forced historians to rewrite transoceanic contact narratives and recognize the maritime skill and range of Norse explorers in the medieval world. It also opened new discussions about interactions with Indigenous peoples, long underestimated in traditional histories.

5. 5. The Indus Valley’s Urban Planning Showing Cities Were More Advanced Than Their Contemporaries

Sara jilani on Wikimedia Commons

When sites like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa were excavated, archaeologists found grid-based city planning, uniform brick standards, sophisticated drainage networks, and multi-story buildings dating as far back as 2600 BCE. These discoveries challenged assumptions that early urban complexity originated in Mesopotamia alone, revealing that the Indus Valley Civilization matched or surpassed other Bronze Age societies in engineering. Their water systems were so advanced that some modern cities still struggle to match their efficiency and organization. The lack of deciphered script means much of their knowledge remains hidden, but their architectural achievements permanently changed how historians view early urban development.

6. 6. The Çatalhöyük Settlement Showing Early Cities Had No Streets or Hierarchies

Kiki K on Pexels

When archaeologists uncovered Çatalhöyük in central Turkey, they found a 9,000-year-old settlement built without streets, doors, or clear social hierarchies, defying assumptions about what early urban life looked like. Residents entered homes through rooftop openings, moved across the city using interconnected roofs, and organized themselves through horizontal, communal structures rather than vertical power systems. This challenged long-held theories that social stratification and formal leadership were prerequisites for large, stable communities. The site proved that early cities could function without kings, temples, or rigid classes, offering a radically different model of how complex societies might have evolved.

7. 7. The Blombos Cave Art Showing Symbolic Thought Began Far Earlier Than Believed

Rabah Al Shammary on Unsplash

In South Africa’s Blombos Cave, researchers discovered engraved ochre pieces and shell beads dating back roughly 75,000 years, revealing symbolic behavior long before early art was thought to exist. These abstract engravings required planning, intentionality, and a capacity for symbolic expression that had previously been attributed only to Upper Paleolithic Europeans. The find forced archaeologists to acknowledge that cognitive modernity did not suddenly appear but evolved gradually and earlier in Africa. Blombos expanded the timeline of human creativity and demonstrated that the roots of symbolic thought are tens of thousands of years deeper than once assumed.

8. 8. The Amazonian Geoglyphs Revealing Complex Societies Thrived in the Rainforest

Grianghraf on Unsplash

For decades, scholars believed the Amazon rainforest could not support large, organized societies due to poor soil quality, but satellite imagery revealed massive geometric earthworks hidden beneath the canopy. These geoglyphs, along with raised fields and engineered landscapes, proved that ancient Amazonians practiced sophisticated land management techniques that supported sizable populations. The discovery overturned the idea of the Amazon as an untouched wilderness, instead showing it was a heavily modified, actively engineered environment. This forced historians to rethink Indigenous innovation and recognize forgotten societies that shaped the rainforest long before European contact.

9. 9. The Hohokam Canal System Showing Pre-Columbian America Mastered Desert Engineering

Faizal Ortho on Pexels

In the American Southwest, the Hohokam built an extensive irrigation network spanning hundreds of miles, allowing them to farm desert lands with remarkable efficiency for over a thousand years. Their canals featured precise gradients and long-distance water control that modern engineers admire, despite the absence of metal tools or draft animals. These discoveries contradicted earlier assumptions that large-scale hydraulic engineering in the region began with European settlers. The Hohokam system proved that Indigenous innovation in North America was not only advanced but sustained on a scale that reshaped archaeological understanding of desert civilizations.

10. 10. The Oldest Known Homo sapiens Fossils Found in Morocco

Philipp Gunz, MPI EVA Leipzig on Wikimedia Commons

The discovery of 300,000-year-old Homo sapiens fossils at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco shocked anthropologists because it pushed the origin of modern humans back by over 100,000 years and far outside eastern Africa, where they were long believed to have evolved. These remains showed a mix of modern and archaic traits, suggesting that our species evolved through a more widespread, networked process rather than emerging from one single region. This challenged the tidy, linear narratives of human evolution and replaced them with a far more complex picture of gradual development across the entire continent. The find redefined both human origins and the geographic scope of early Homo sapiens.

11. 11. The Liangzhu Hydraulic System Showing Early China Had Engineers on Par With Later Dynasties

Siyuwj on Wikimedia Commons

When the ancient city of Liangzhu was excavated, archaeologists discovered a sprawling network of dams, levees, and reservoirs dating back more than 4,500 years, revealing water-control engineering far more advanced than expected for the Neolithic period. These structures were built with precision earthworks that required coordinated labor, complex planning, and an understanding of hydrology that seemed out of place for a society long assumed to be agriculturally simple. The scale of the system rivaled irrigation works from much later dynasties, forcing researchers to revise assumptions about when large-scale social organization and state-level planning first emerged in China. Liangzhu’s mastery of water reshaped the timeline of East Asian technological development and demonstrated that early societies could achieve engineering sophistication long before written history recorded it.

12. 12. The Neanderthal Cave Art Showing They Had Symbolic Minds Like Ours

Jeff Walker on Flickr

For decades, Neanderthals were portrayed as cognitively inferior to Homo sapiens, but the discovery of cave paintings in Spain dated to more than 64,000 years ago overturned that stereotype completely. These hand stencils, geometric marks, and painted formations predated the arrival of modern humans in the region, confirming that Neanderthals produced symbolic art independently rather than borrowing the practice from us. This finding rewrote the idea that symbolic expression was uniquely human, proving instead that our closest relatives shared capacities for abstraction, communication, and ritualized creativity. The implications are profound, suggesting a world where multiple human species developed cultural traditions far richer than once believed.

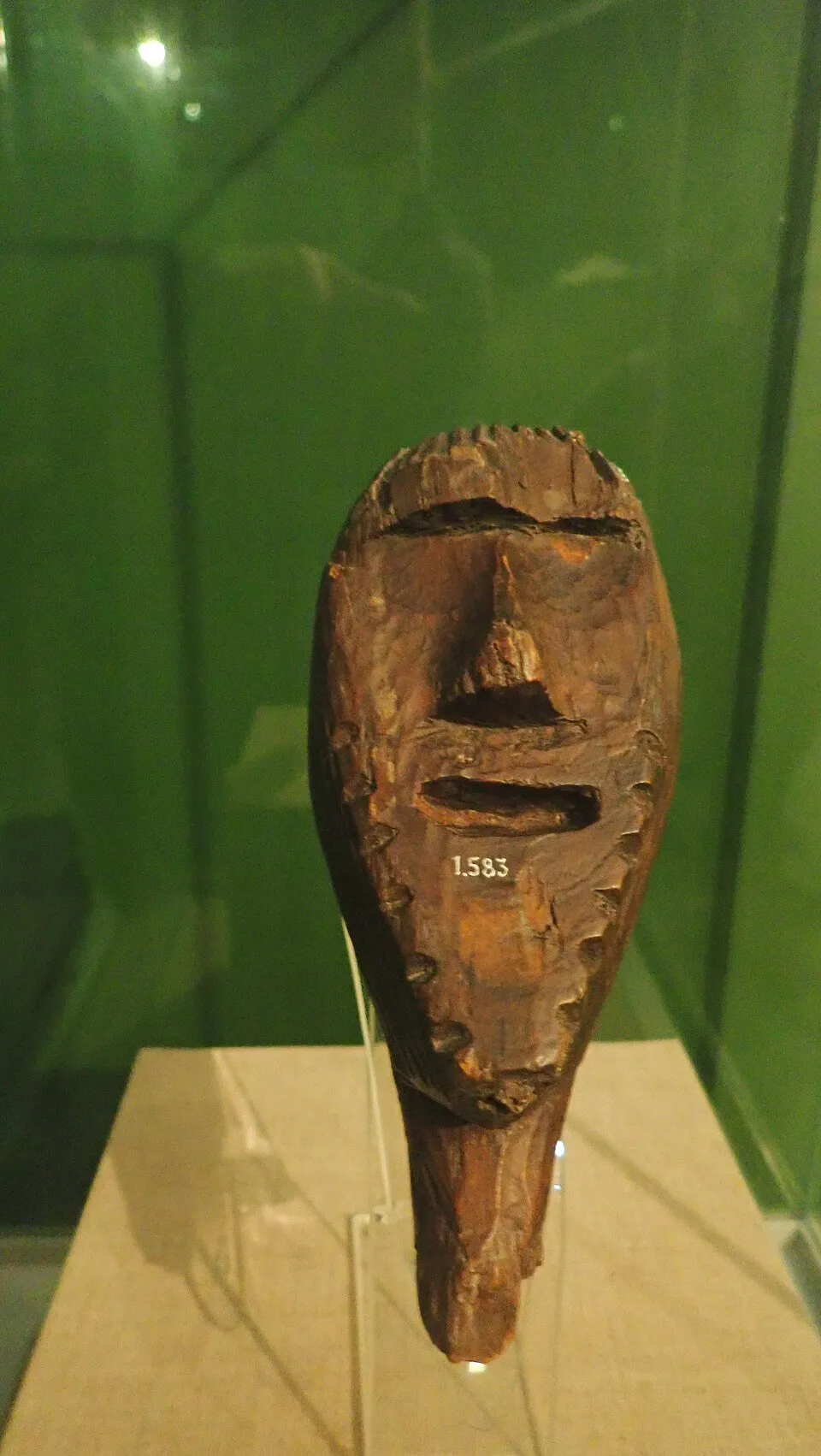

13. 13. The Shigir Idol Showing Advanced Symbolism Twice as Old as Expected

Леонид Макаров on Wikimedia Commons

Unearthed from a Siberian peat bog, the Shigir Idol is a wooden sculpture more than 11,000 years old, covered in geometric carvings and motifs that required a symbolic language far older than archaeologists thought existed. Its intricate patterns suggest ritual meaning, lineage memory, or mythological storytelling at a time when humans were assumed to focus solely on survival. The Idol’s survival in waterlogged soil preserved details that challenge long-standing timelines of artistic and symbolic development across Eurasia. The artifact forced researchers to accept that early hunter-gatherers possessed a level of cultural complexity previously attributed only to later sedentary societies.

14. 14. The Paleolithic “Venus” Figurines Showing Shared Symbolism Across Vast Distances

Archäologisches Museum Hamburg und Stadtmuseum Harburg on Wikimedia Commons

Small Upper Paleolithic figurines depicting human forms have been found across Europe and parts of Asia, many created more than 25,000 years ago using remarkably similar artistic conventions despite enormous geographic separation. This widespread stylistic continuity challenged assumptions that early groups were isolated and culturally distinct, instead revealing interconnected symbolic traditions that may have spanned entire continents. The figurines demonstrate shared ideals of fertility, identity, or ritual meaning long before formal writing or centralized cultures existed. Their distribution suggests that social networks, migration routes, or knowledge exchange among early humans were far more extensive than previously imagined.

15. 15. The Sulawesi Cave Art Proving Asia Was a Cradle of Early Creativity

Sanjay P. K. on Flickr

When archaeologists dated hand stencils and animal paintings in Indonesia’s Sulawesi caves to at least 45,500 years old, they realized that some of the world’s earliest figurative art didn’t come from Europe as widely assumed, but from Southeast Asia. This discovery dismantled Eurocentric timelines that placed symbolic creativity squarely in the Western tradition and revealed that artistic expression likely emerged wherever early humans migrated. The paintings depict wild animals with a level of naturalism and stylistic intent that rivals European Paleolithic masterpieces, demonstrating a shared global capacity for art. These findings broadened humanity’s artistic origin story and proved that creativity blossomed across regions rather than radiating from a single cultural center.