18 Ancient Beliefs That Resemble Modern Scientific Ideas

The striking similarities between ancient philosophical speculations and modern scientific concepts underscore humanity's enduring quest to understand the universe through observation and rational deduction.

- Alyana Aguja

- 13 min read

This collection explores 18 profound connections between the speculative philosophical beliefs of ancient thinkers and the core principles of modern science. These historical precursors foreshadow fundamental physics and chemistry concepts centuries before empirical validation. These conceptual overlaps illustrate that the spirit of scientific inquiry has a lineage stretching back millennia. The persistence of these concepts, despite the lack of modern experimental tools, confirms the power of human reason and the continuity of intellectual exploration from ancient philosophy to contemporary research, offering a compelling narrative of how foundational knowledge emerges and evolves across historical epochs.

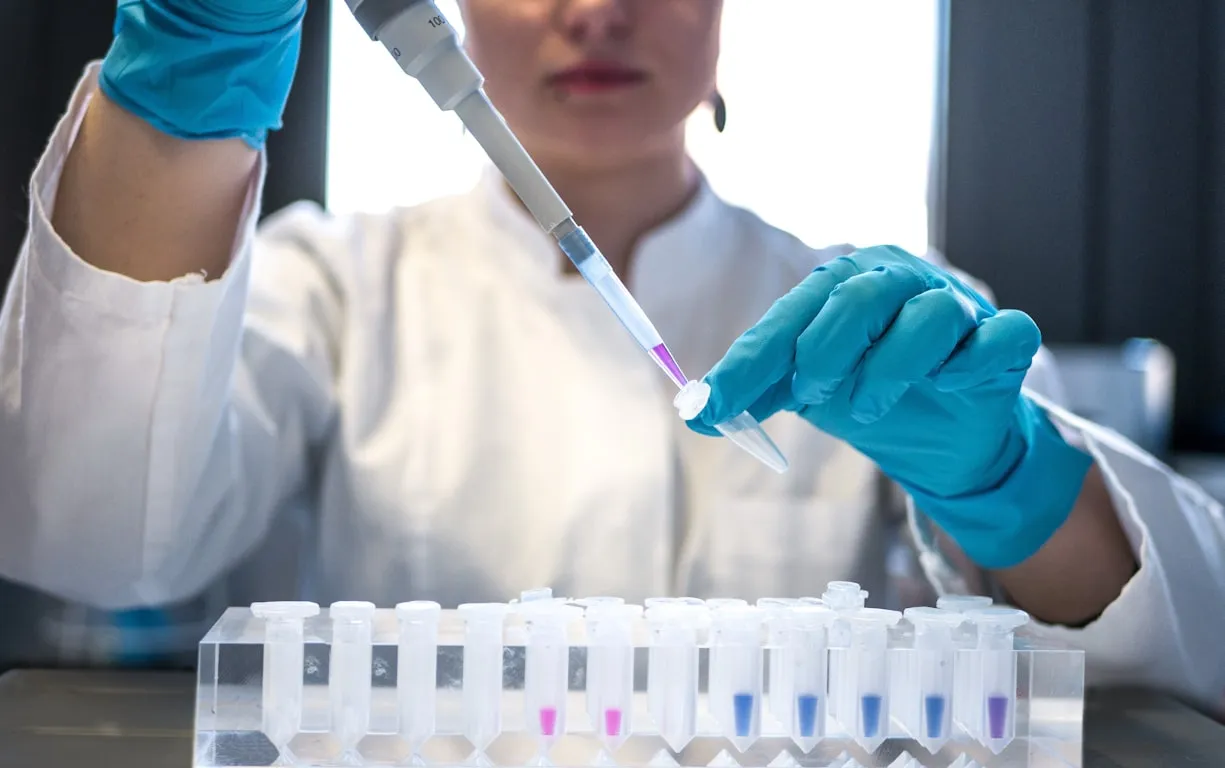

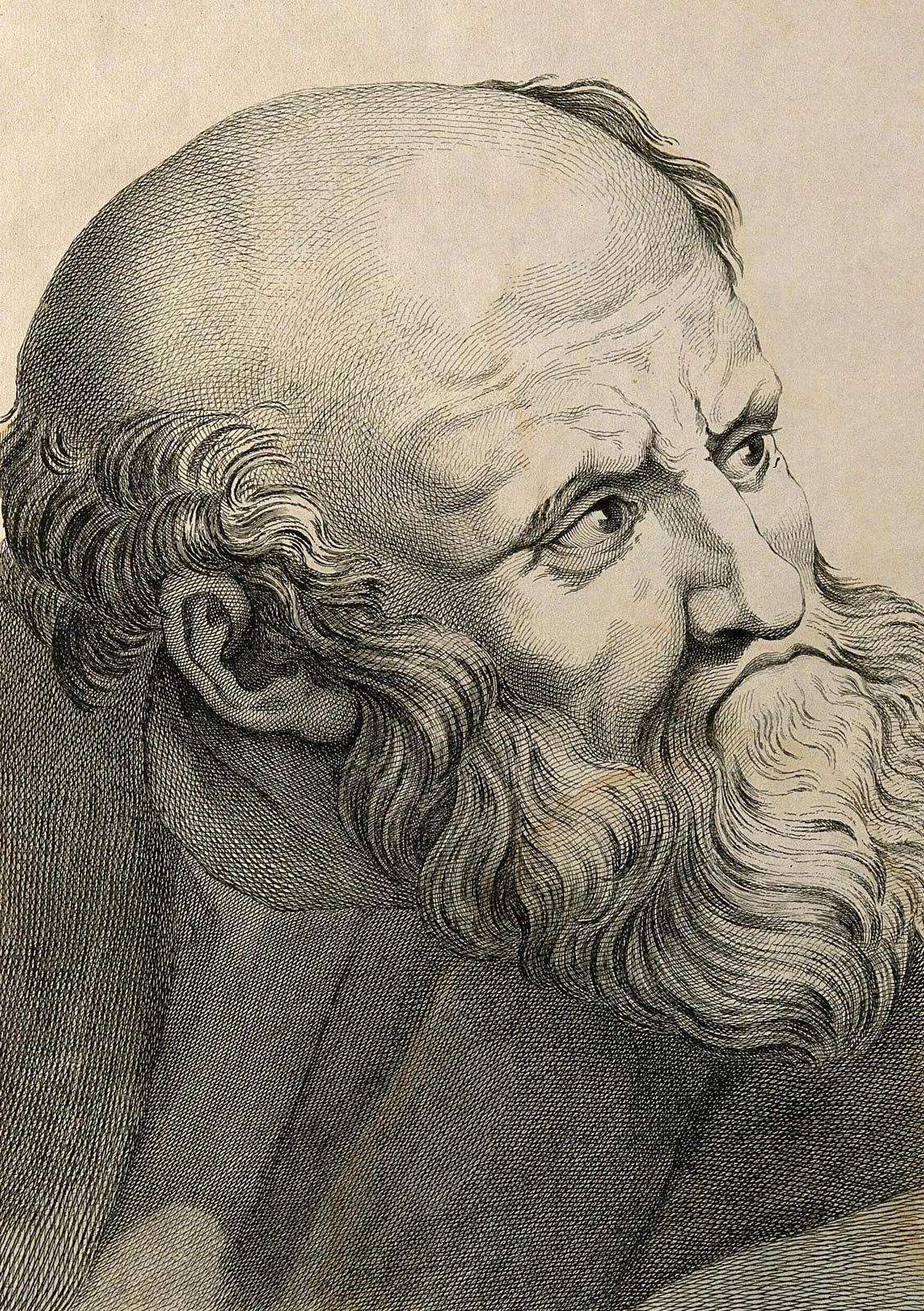

1. 1. The Atomic Theory of Democritus

Image from Steemit

The ancient Greek philosopher Democritus, active around the 5th century BCE, proposed that all matter in the universe was composed of tiny, indivisible, and indestructible particles he called atomos. This groundbreaking idea was purely philosophical, stemming from thought experiments, but it remarkably foreshadows the modern scientific understanding of matter being made up of atoms, the fundamental building blocks of chemistry and physics. He suggested that differences in material properties, such as hardness or color, arose from the size, shape, and arrangement of these countless minute particles. This early, intuitive grasp of an ultimate, fundamental particle represented a monumental leap in conceptualizing the material world, laying the groundwork for future scientific inquiry into the nature of reality, even though experimental methods were absent at the time. Modern science has confirmed the existence of atoms and their essential role in all physical and biological processes. While his theory lacked the empirical rigor of modern science, the core concept of fundamental, unchangeable particles remains a cornerstone of our current scientific worldview.

2. 2. Parmenides’ Principle of Conservation

Image from Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The Presocratic philosopher Parmenides of Elea (c. 5th century BCE) is famous for his statement that “nothing comes from nothing” and that change is essentially an illusion. While his conclusion that the universe is a single, unchanging entity seems contrary to observation, his underlying principle strongly resonates with modern conservation laws in physics. He argued that existence (or Being) could neither arise from non-existence (non-Being) nor pass away into it, suggesting a fundamental permanence to reality. This philosophical stance, which denied true creation or destruction, implied a core truth about the substance of the cosmos. Parmenides’ insistence on the uncreated and indestructible nature of reality, despite being couched in metaphysical terms, captures the essence of these scientific laws, which dictate that fundamental quantities are conserved across all physical and chemical transformations.

3. 3. The Hellenistic Concept of Pneuma and Nerves

Image from PhysioStrength Physical Therapy

Ancient Greek and Hellenistic physicians developed the concept of pneuma (literally “breath” or “spirit”) to explain biological functions. They believed that pneuma, drawn from the air, was processed into different forms—the pneuma psychikon (animal or psychic spirit) was located in the brain and transmitted through the hollow nerves to initiate movement and sensation. They thought this spirit was a vital fluid that traveled along the neural pathways. Although the mechanism was incorrect, involving spirits instead of electrical signals, the ancient anatomists correctly identified the nerves as the structures responsible for conveying signals between the brain and the body’s periphery, which is a core tenet of modern neuroscience. This identification of the physical conduits of sensation and action provided a rudimentary, structural understanding of the nervous system’s function, anticipating its true role.

4. 4. Aristarchus’ Heliocentric Model

Image from High Altitude Observatory

In the 3rd century BCE, the Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos proposed a radical cosmological model that placed the Sun at the center of the universe, with the Earth and other planets revolving around it. This heliocentric model directly contradicted the prevailing geocentric (Earth-centered) view held by most ancient philosophers, including the influential Aristotle and Ptolemy. Aristarchus’ reasoning was based on geometrical analysis of the sizes and distances of the Sun and Moon, which led him to conclude the Sun must be vastly larger than the Earth. This proposal is a stunning anticipation of the modern Solar System model, which was only widely accepted after the work of Copernicus over 1,700 years later. Although his model lacked detailed mathematical rigor, the fundamental concept that the Earth orbits the Sun—not the other way around—is a foundational pillar of modern astronomy. Aristarchus’ insight demonstrates a profound ability to deduce a complex truth about the cosmos based on limited observational data, prioritizing reason and mathematical inference over sensory experience.

5. 5. Anaximander’s Theory of Evolution

Image from Britannica

The Presocratic philosopher Anaximander of Miletus (c. 610–546 BCE) speculated about the origins of life in a manner that surprisingly foreshadows modern evolutionary theory. He proposed that life initially emerged from the primordial wet element, and, crucially, that the first human beings were not born as they are now. Instead, he suggested that humans originated inside fish-like creatures, which they inhabited until they were capable of fending for themselves on dry land. This implied that species could transform over time. This concept contains two key elements of modern biology: the idea that life originated in the sea and the notion of descent with modification, or evolution, where organisms change and adapt to their environment. Anaximander’s theory posited a mechanism for the historical development of species, acknowledging that the present form of life was a result of past transformations and environmental necessity. Although lacking the mechanism of natural selection, his work represented a significant early attempt to explain the diversity of life through purely natural processes.

6. 6. Vitruvius’s Acoustic Design and Wave Theory

Image from Geniuses.Club

The Roman architect Vitruvius, in his seminal work De Architectura (c. 15 BCE), detailed principles for designing theaters, including rules for optimal acoustics. He described how sound, much like water waves, spreads outward in concentric circles from a central point of articulation. He specifically noted the importance of sound wave reflection and absorption, suggesting ways to counter echoes and dead zones by using bronze vessels. Vitruvius’s observations on the spreading of sound waves are consistent with the modern wave theory of sound, which describes sound as a mechanical wave propagating through a medium. His practical advice for manipulating sound in an architectural space reflects an intuitive, albeit non-mathematical, understanding of acoustics and wave interference. The focus on how sound interacts with the physical environment demonstrates an early, applied grasp of basic wave physics principles.

7. 7. Empedocles’ Theory of Light and Vision

Image from Britannica

Empedocles (c. 490–430 BCE) proposed a theory of light and vision that had an astonishingly modern component. He suggested that light travels from a source to the eye, but he also theorized that the eye emitted its own “effluences” or rays. This was known as the emanation or extramission theory, which was later rejected in favor of the intromission theory (light entering the eye). The modern similarity lies in the concept of light as a wave-particle duality. Empedocles’ idea mirrors the complex nature of light. While the “eye-rays” are scientifically incorrect, the notion that light involves a two-way interaction or dual property resonates with the modern understanding that light behaves as both waves (traveling outward) and photons (discrete packets or particles) depending on how it’s measured.

8. 8. Hippocrates’ Theory of Humors and Disease

Image from Biography

The foundational medical theory of Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE) centered on the four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. He proposed that disease was not a divine punishment but was caused by an imbalance in these humors within the body. Crucially, his approach involved observing the patient’s symptoms, diet, and environment to recommend treatments like rest, exercise, or a change in diet, aiming to restore balance. This ancient concept of imbalance foreshadows the modern medical understanding of homeostasis, the body’s ability to maintain a stable internal environment. Modern medicine treats disease by identifying and correcting physiological imbalances. Hippocrates’ emphasis on holistic observation and the role of lifestyle factors in health and disease aligns with modern preventative medicine and the acknowledgment of complex systemic interactions.

9. 9. The Stoic Doctrine of Cosmic Cycles

Image from Daily Stoic

The Stoics, a school of philosophy flourishing from the 3rd century BCE, held the belief that the universe underwent endless, repeating cycles of creation and destruction. They envisioned a periodic ekpyrosis (conflagration), where the universe would be consumed by fire and then reborn, identical to the previous cycle. This was a process of eternal recurrence, where the universe was cyclical and self-sustaining. While the Stoic ekpyrosis is not a direct match for any specific modern theory, their concept of an endlessly changing, yet fundamentally cyclical, universe touches upon modern cosmological ideas. Theories such as the oscillating universe and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics both explore concepts of cosmic repetition or infinity. The Stoic emphasis on the universe’s internal, cyclical mechanism aligns with a scientific search for an ultimate, deterministic, and self-regulating cosmic process.

10. 10. The Babylonian Calculation of Planetary Motion

Image from National Geographic

Ancient Babylonian astronomers, particularly from the 7th to 4th centuries BCE, developed highly sophisticated mathematical methods to predict the positions of the planets, the timing of eclipses, and the length of the lunar month. They used arithmetic and geometric calculations, including the use of abstract mathematical concepts and tables, to create complex predictive models for the irregular movements of celestial bodies across the sky. These ancient predictive techniques strongly resemble the modern scientific use of mathematical modeling and algorithms in celestial mechanics and astrophysics. The Babylonians treated astronomical data like a mathematical problem to be solved with predictive precision, establishing a purely quantitative approach to the heavens. Their development of abstract mathematical methods for calculating phenomena, rather than relying solely on observational data, established a precedent for theoretical and computational science.

11. 11. Al-Haytham’s Scientific Method

Image from Kids encyclopedia facts - Kiddle

The Arab polymath Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen) in the 10th-11th centuries CE, made crucial contributions to the fields of optics and methodology. In his Book of Optics, he correctly theorized that vision results from light entering the eye (intromission theory) and rejected the ancient emission theories. More significantly, he championed a systematic approach to inquiry, involving observation, experimentation, and the use of mathematics, insisting that theories should be proven by evidence. Al-Haytham’s rigorous and skeptical approach is widely recognized as an early formulation of the modern Scientific Method. He emphasized repeatable experiments and the necessity of empirical proof to validate hypotheses, a critical departure from purely philosophical or deductive reasoning. His work on optics, including his investigation of refraction and the camera obscura, laid the empirical and methodological groundwork that would later be adopted by European scientists during the Scientific Revolution.

12. 12. Early Concepts of Immunity in Thucydides

Image from History.com

The Greek historian Thucydides, writing about the devastating Plague of Athens in the 5th century BCE, made an important observation regarding those who survived the disease. He noted that those who had recovered from the plague could safely nurse the sick without contracting the illness again. This observation was recorded at a time when understanding of disease transmission was practically nonexistent. This ancient observation provides an early description of acquired immunity, a foundational principle of modern immunology. The fact that people who survive a disease are protected from subsequent infection is the basis for vaccination and the entire field of disease prevention. Thucydides identified a biological mechanism that is a key defense system of the body against pathogens.

13. 13. Vaisheshika School’s Theory of Movement

Image from VedicFeed

The ancient Indian Vaisheshika school of philosophy, dating back to at least the 6th century BCE, developed a detailed theory of atomism and motion. They classified motion (karma) into five distinct categories: throwing upward, throwing downward, contracting, expanding, and traveling. Furthermore, they posited that movement was caused by a specific impetus or force (vega) which must be applied for the movement to occur. The Vaisheshika concept that movement requires an impetus to initiate and sustain it bears a strong resemblance to Newton’s First Law of Motion (Inertia) and the role of force in classical mechanics. While their understanding was qualitative and metaphysical, they grasped the essential idea that a force or intrinsic quality is required to change an object’s state of motion, anticipating the mechanical principles later formalized in Western science.

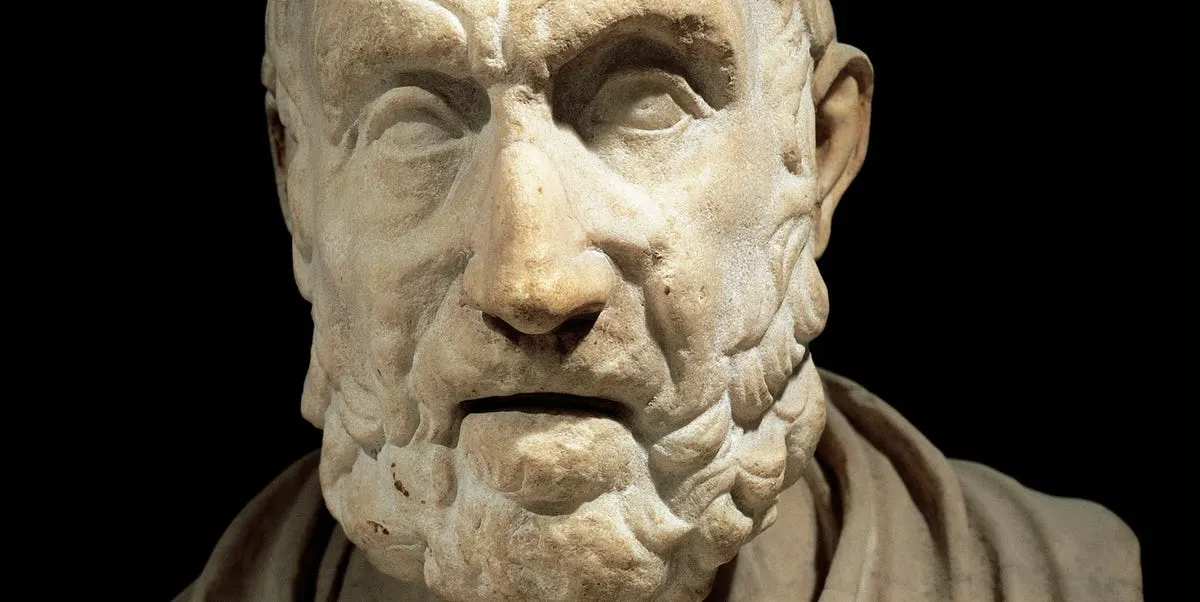

14. 14. Aristotle’s Classification of Life

Image from Britannica

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (4th century BCE) was arguably the first true biologist, systematically classifying living things into a hierarchical structure called the Scala Naturae (Ladder of Nature). He categorized organisms by their complexity, from plants at the bottom, through various animals, to humans at the top. He also distinguished between different forms of reproduction and the anatomical features of thousands of species. Aristotle’s meticulous collection, observation, and hierarchical organization of life represent the beginning of modern taxonomy and biology. His classification system, though superseded by Linnaeus’s, established the crucial practice of grouping organisms based on shared physical characteristics. The systematic approach to understanding biological relationships and diversity remains the foundation of evolutionary and systematic biology today.

15. 15. The Sphericity of the Earth

Image from Space

The idea that the Earth is a sphere was first definitively argued by Greek philosophers, including Pythagoras in the 6th century BCE and later solidified by Aristotle and Eratosthenes. Aristotle provided observational evidence, such as the curved shadow the Earth casts on the Moon during a lunar eclipse and the way certain stars disappear below the horizon as one travels south. Eratosthenes later calculated the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy. This ancient realization is a cornerstone of modern geodesy and astronomy. The understanding that the Earth is a three-dimensional globe, rather than a flat disc, corrected a fundamental misconception about our place in the cosmos. The methods used, such as observing shadows and astronomical events, exemplify early empirical science and mathematical inference to determine a physical property of a celestial body.

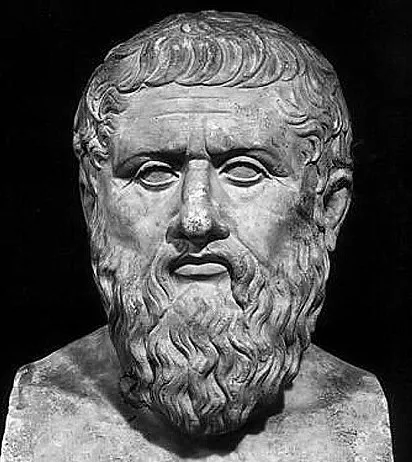

16. 16. The Timaeus’s Geometrical Structure of Matter

Image from The Great Thinkers

In Plato’s dialogue Timaeus (c. 360 BCE), he proposed a highly theoretical and geometrical model for the structure of matter. He associated the four classical elements with specific Platonic Solids. He suggested that the smallest particles of these elements possessed these perfect, geometrical shapes, dictating their properties. While factually incorrect, this concept of fundamental, geometrical building blocks that determine material properties remarkably anticipates modern crystallography and the study of molecular geometry. Modern science knows that atoms bond in specific, fixed geometrical arrangements that define the macroscopic properties of substances. Plato’s idea represents an early, sophisticated attempt to explain physical properties through an underlying mathematical structure.

17. 17. Lucretius’s Theory of Seeds and Disease

Image from Britannica

The Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius (1st century BCE), in his work De Rerum Natura, eloquently described the atomic theory of the Greeks and applied it to explain the spread of disease. He speculated that “seeds of disease” (semina morbi) were invisible, airborne particles that could enter the body and cause sickness. He argued that these minute bodies were specific to certain illnesses and could be exhaled and inhaled. Lucretius’s concept of invisible, airborne “seeds of disease” is a striking pre-scientific description of the germ theory of disease, the foundational concept of modern microbiology and epidemiology. His idea that tiny, non-living or living particles transmit illness through the air or direct contact anticipated the discovery of viruses and bacteria by over 1,800 years. His work provided an atomistic explanation for biological contagion.

18. 18. Early Ideas of Climate Change in Theophrastus

Image from Britannica

Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BCE), a student of Aristotle and the “father of botany,” wrote about the influence of environment and climate on plant life. He made observations suggesting that local climates could change over long periods, noting how draining marshes and expanding irrigation seemed to make a region warmer and more arid. He noted human activity could alter local weather. Theophrastus’s observations about the correlation between human activity (like drainage) and shifts in local temperature and aridity are an early, perceptive recognition of anthropogenic climate change. His work highlights the ancient awareness that large-scale environmental modifications can have measurable, long-term consequences on weather patterns. This ancient insight into the feedback loops between land use and climate foreshadows modern climatology.