18 Instances Where Nature Outperformed Human Technology

Nature consistently demonstrates superior, sustainable, and highly efficient solutions across materials science, engineering, and sensory systems, providing invaluable blueprints for human technological advancement.

- Alyana Aguja

- 10 min read

This article explores 18 distinct instances where biological and natural processes exhibit a performance superiority over contemporary human-designed technology, highlighting nature’s mastery in areas like material science, sensory detection, energy efficiency, and structural engineering. From the self-cleaning Lotus Effect to the unparalleled strength of spider silk and the passive climate control of termite mounds, these examples illustrate an elegant efficiency that is often non-toxic, self-repairing, and operates under ambient conditions without external power inputs. These natural designs serve as powerful lessons in optimized, resilient system performance.

1. 1. The Lotus Effect (Self-Cleaning Surface)

Image from ATRIA Innovation

The lotus leaf maintains a pristine appearance even in muddy environments due to a phenomenon known as the Lotus Effect. This is achieved through a superhydrophobic surface structure composed of microscopic bumps coated with wax, causing water droplets to bead up and roll off. This natural mechanism provides a self-cleaning surface without the need for chemical agents or mechanical scrubbing. Human technology is still perfecting synthetic superhydrophobic coatings to achieve the same durability, cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness as the lotus. Nature’s design is passive, energy-free, and remarkably long-lasting, a testament to superior material and structural engineering that operates flawlessly across various environmental conditions without maintenance or power inputs.

2. 2. Spider Silk (Tensile Strength)

Image from Spin Off

Spider silk is a protein fiber renowned for its extraordinary combination of strength and elasticity. It possesses a tensile strength comparable to steel but is five times lighter, and it can stretch up to 40% of its original length without breaking. This makes it one of the toughest materials known, vastly superior to any synthetic fiber like Kevlar in its ability to simultaneously absorb energy and resist rupture. Scientists have long sought to artificially spin a fiber with the same molecular structure and performance as natural spider silk, but commercial, large-scale production of a perfect synthetic equivalent remains a significant challenge. The spider’s ability to produce this material at ambient temperature and pressure, using only water and proteins, demonstrates a mastery of green chemistry far beyond current industrial methods.

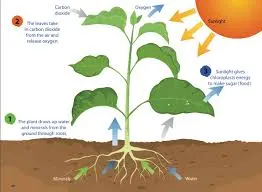

3. 3. Photosynthesis (Solar Energy Conversion)

Image from Smithsonian Science Education Center

Photosynthesis is the process by which plants, algae, and some bacteria convert light energy into chemical energy (sugars), using carbon dioxide and water. Natural photosynthesis typically achieves a solar energy conversion efficiency of up to 6% in terms of total solar radiation and around 30-40% of the light the plant actually absorbs, but it does so while being completely self-repairing, self-assembling, and self-regulating. Our best commercial solar panels achieve higher peak efficiencies (upwards of 20-25%), but they require complex, energy-intensive manufacturing processes and degrade over time. The biological mechanism operates with remarkable stability, self-repair, and a regenerative, scalable system that cycles nutrients and self-replicates, offering a blueprint for truly sustainable energy harvesting.

4. 4. Geckos’ Feet (Dry Adhesion)

Image from Fear Free Happy Homes

The incredible ability of geckos to adhere to almost any surface, including smooth glass, comes not from sticky liquids but from millions of microscopic hairs called setae on their toes. These hairs branch into even finer tips called spatulae, which generate sufficient van der Waals forces to support the gecko’s weight, enabling non-toxic, residue-free, and instantly reversible dry adhesion. The development of synthetic adhesives that can match the gecko’s performance is a major focus in robotics and manufacturing. Nature solved the problem of reversible, non-contact, and residue-free gripping billions of years ago with an elegant physical structure that is unparalleled by current mechanical or chemical solutions.

5. 5. Termite Mounds (Passive Climate Control)

Image from Frontiers

The towering mounds built by certain termite species are not just homes but sophisticated examples of architectural engineering for climate control. These structures use a network of tunnels and vents to regulate internal temperature and humidity through passive ventilation, maintaining a stable, habitable environment despite drastic external weather fluctuations and without any external power source. This natural air conditioning inspired the design of the Eastgate Centre in Harare, Zimbabwe, but the termite mound’s system is inherently more complex, self-maintaining, and scalable across various sizes without complex sensors or moving parts. It serves as a superior model for biomimetic sustainable architecture, showcasing efficient, zero-energy thermal regulation.

6. 6. Whale Flipper Tubercles (Fluid Dynamics)

Image from Britannica

The bumpy leading edge or tubercles on the flippers of humpback whales significantly improve their maneuverability. These bumps control water flow, delaying stall and increasing lift and reducing drag by up to 32% compared to a smooth-edged flipper. This allows the massive mammals to make sharp turns while feeding, an aerodynamic and hydrodynamic marvel. Engineers are applying this principle, known as the “Tubercles Effect,” to the design of wind turbine blades, airplane wings, and cooling fans to enhance efficiency and reduce noise. Nature’s solution for fluid control, implemented through a simple structural modification, outperforms the traditional smooth-surface designs favored by human technology.

7. 7. Pit Vipers’ Heat Sensing (Infrared Detection)

Image from Bali.com

Pit vipers possess specialized organs, known as pit organs, that allow them to “see” the heat signature of prey, giving them an incredibly sensitive form of passive infrared detection. These organs can detect temperature differences as small as 0.003°C across a wide field of view. Our most sensitive thermal imaging cameras and military-grade infrared sensors require complex cooling systems, significant power, and sensitive electronic components to achieve a fraction of the pit viper’s sensitivity. The snake’s biological sensor is self-contained, operates without active cooling, and demonstrates a superior level of passive infrared sensitivity and robustness.

8. 8. Shark Skin (Drag Reduction)

Image from Britannica

Shark skin is covered in microscopic, tooth-like scales called dermal denticles, which are aligned to channel water flow over the shark’s body. These riblets reduce hydrodynamic drag by disrupting turbulent flow. This natural design has inspired “riblet technology,” applied to competition swimwear, ship hulls, and aircraft coatings to reduce friction and save fuel. While human application of the riblet concept has shown success, the shark’s skin is a living, self-repairing surface that dynamically adjusts its structure, offering a level of adaptive performance that synthetic coatings cannot yet match.

9. 9. Abalone Shell (Toughness and Strength)

Image from Simply Shells

The abalone shell, or nacre (mother-of-pearl), is composed of microscopic tiles of calcium carbonate separated by thin layers of protein, resembling a brick-and-mortar structure. This arrangement makes the shell incredibly strong and tough, preventing cracks from propagating through the material. Engineers are striving to replicate this composite material architecture to create lightweight, super-tough ceramics for body armor and structural applications. The abalone’s method of layering materials at the nanoscale, synthesized from readily available components in seawater and at ambient temperature, represents a pinnacle of natural material science that remains unsurpassed.

10. 10. Namib Desert Beetle (Water Condensation)

Image from Science

The Namib Desert beetle has evolved a unique mechanism to collect water from the fog in its arid environment. Its back is covered with alternating hydrophilic bumps and superhydrophobic troughs. This structure allows fog droplets to condense on the bumps, grow large, and then roll down the water-repelling troughs directly into the beetle’s mouth. This design is a direct inspiration for fog-harvesting nets and water collection systems aimed at providing drinking water in dry coastal regions. The beetle’s ability to selectively manipulate water droplets and manage phase transition with a simple, robust body structure offers a significantly more efficient and elegant solution for atmospheric moisture capture than most current technologies.

11. 11. Kingfisher’s Beak (Aerodynamic Design)

Image from Roundglass Sustain

The streamlined, sharp, and non-splashing entry of the kingfisher’s beak into water minimizes both drag and splash. The bird’s unique bill design, a narrow tip widening to a base, allows it to transition from air to a denser medium with remarkable efficiency and minimal resistance. This natural shape was a crucial inspiration for the nose cone of the Japanese Shinkansen bullet train, which solved the problem of the shockwave and sonic boom created when the old, blunt-nosed trains exited tunnels. The kingfisher’s beak is a masterpiece of aerodynamic and hydrodynamic engineering, optimizing travel across two media simultaneously without complex mechanical adjustments.

12. 12. Fireflies’ Light (Bioluminescence Efficiency)

Image from Scientific American

Fireflies produce light through bioluminescence, a chemical reaction that converts nearly 100% of the energy into light, resulting in a cold light with almost zero heat loss. This near-perfect efficiency is far superior to human-made incandescent bulbs, which lose over 90% of their energy as heat, and even surpasses modern LED technology, which still generates waste heat. The firefly’s mechanism is a focus of research in developing ultra-efficient lighting and bio-indicators, demonstrating a pathway to achieving total energy conversion for light emission. Its chemical-based, highly efficient method for producing light at ambient temperatures shows that nature has perfected a system of illumination that human technology has not yet matched in purity and efficiency.

13. 13. Tree Roots (Soil Stabilization and Filtration)

Image from Root Barrier Store

The intricate network of tree roots provides unparalleled soil stabilization, preventing erosion and massive landslides by binding the earth. Furthermore, the root systems, often in symbiosis with fungi, act as highly effective, self-repairing, and self-regulating natural filtration systems, cleaning water by absorbing nutrients and trapping pollutants. Engineers use various civil engineering techniques, such as retaining walls and geotextiles, for erosion control, but these solutions often lack the flexibility, self-healing capacity, and widespread effectiveness of a natural forest or mangrove system. The tree’s root architecture offers a sustainable, cost-effective, and ecologically superior solution for both geotechnical and hydrological management.

14. 14. Peacock Feathers (Structural Color)

Image from Britannica

The vibrant, iridescent colors of a peacock’s feathers are not created by pigments but by structural color, which relies on the microscopic physical structure of the barbules to selectively reflect specific wavelengths of light. This mechanism creates colors that are extremely durable, fade-resistant, and shift in appearance with viewing angle. The pursuit of structural color in technology aims to replace chemical dyes in paints, textiles, and displays to create environmentally friendly, non-fading colors without toxic ingredients. Nature’s approach to color generation through physics rather than chemistry yields a permanent, energy-efficient, and superior aesthetic that human industry is only beginning to harness.

15. 15. Mussels’ Byssal Threads (Underwater Adhesion)

Image from Allrecipes

Mussels attach themselves firmly to wet, challenging surfaces, such as rocks and pilings, using strong, elastic, and water-resistant byssal threads. The adhesive plaques at the end of these threads secrete a unique, complex protein-based cement that cures rapidly in a saltwater environment, providing a bond that is both robust and flexible. Developing an adhesive that performs reliably in wet, salty, or oily environments is a major goal for surgical, marine, and dental applications. The mussel’s ability to engineer an ultra-strong, non-toxic, and biocompatible underwater glue is a natural engineering feat that significantly outperforms current commercial marine epoxies and medical adhesives.

16. 16. Bird Navigation (Magnetic Field Sensing)

Image from Britannica

Many species of migratory birds possess a remarkable ability to sense the Earth’s magnetic field and use it, along with stellar and solar cues, for long-distance navigation with astonishing accuracy. This biological compass allows them to navigate across continents, even when visibility is poor, without the need for maps or GPS satellites. Our most advanced navigational systems rely on a network of orbiting satellites (GPS/GNSS) and sensitive, power-hungry electronic magnetometers. The bird’s navigation system is passive, energy-efficient, and instantly integrated with other senses, representing an unparalleled, robust, and completely self-contained biological system for global positioning.

17. 17. Wood (Self-Assembly and Sustainability)

Image from Home and Garden - HowStuffWorks

Wood, the material produced by trees, is the ultimate example of a strong, lightweight, and self-assembling composite material. It is naturally synthesized from atmospheric carbon dioxide and water, is completely biodegradable, and provides superior strength-to-weight ratios compared to many steel or concrete structures. While we are developing 3D-printed materials and advanced composites, nothing yet matches the sustainability, renewability, and ambient-temperature fabrication of wood. It represents a decentralized, net-zero-carbon manufacturing process that yields a structural product capable of self-repair and complete recycling back into the environment.

18. 18. Human Ear (Sound Processing and Filtering)

Image from Live Science

The human ear and associated neural processing systems are an engineering marvel, capable of discerning extremely subtle variations in sound frequency and amplitude. This sophisticated acoustic processing allows for comprehension of a single voice in a crowded room. Despite advancements in digital signal processing, even the most complex microphone arrays and noise-canceling headphones struggle to match the human ear’s combination of sensitivity, dynamic range, and cognitive filtering capabilities. The ear’s passive, robust, and highly adaptive sensory performance remains a benchmark for superior, real-time auditory processing technology.